I Am Sky: On Emptiness, or Shunyata

written by Laura Cherry

I am privileged to know an extraordinary and precocious six-year-old with a deft imagination. One autumn afternoon, I watched him construct a makeshift umbrella by piercing large leaves on one end of a tree branch and holding it over his head. On another day, he showed me the “special tree” outside his house, excitedly pointing out naturally occurring notches in the trunk that served as furniture for insects and cup holders for human visitors. He is known to stand outside and make grand, sweeping statements such as, “I am grass! I am this tree. I am this chair. I am water! I am sky!”

This may sound like childish nonsense, but it reveals a profound understanding of one of the most difficult Buddhist teachings: shunyata, or emptiness, as given to us in the Heart Sutra. This youngster implicitly understands the concept of interbeing: the notion that everything in the universe is inherently connected to everything else. This boy is, in fact, made of trees, water, and sky. Without them, he couldn’t exist.

From the Heart Sutra:

“Listen, shariputra,

form is emptiness, and emptiness is form.

Form is not other than emptiness, emptiness is not other than form.

The Heart Sutra, given to us by the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, delivers the essential Buddhist teachings on emptiness, or shunyata (SHOON-ya-ta). Although the Heart Sutra is among the best-known Buddhist teachings, it remains mysterious and misunderstood, particularly in the West. In English, the word emptiness suggests nihilism (the belief that life is meaningless), erasure, or scarcity. It typically connotes something negative, literally—a lack of something which should be present, an absence of a thing we need. We go out of our way to ensure that certain things in our lives are not empty, such as our bank account, our gas tank, or our refrigerator. Parents mourn an empty nest. When we feel down or depressed, we may express that we feel empty inside. In these situations, the word “empty” refers to an absence of something tangible and specific: no money, no gas, no food, no children, no feelings. But in the Buddhist teachings, when we ask, “What is this empty of?” the answer is always, “Empty of a separate self.”

“To be is to inter-be. You cannot just be by yourself alone. You have to inter-be with every other thing. This sheet of paper is, because everything else is.” —Thich Nhat Hanh

The Venerable Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh helps us understand shunyata, or emptiness, through the concept of “interbeing.” He famously uses the existence of a single sheet of paper to illustrate how interbeing and emptiness are related.

If we look at a single sheet of paper, he says, we can see that the whole universe is within it. We can see the sunshine that allowed the tree to grow, the earth that nourished its roots, the rainclouds that quenched its thirst. We can also see the logger who cut down the tree and brought it to the mill. We can imagine the paper factory and the clerk at the store where we purchased the paper. If we remove even one of these elements, such as the sunshine, or someone to cut the tree, the piece of paper could not exist as it is.

Returning to the text of the Heart Sutra, form (the sheet of paper) is empty (of a separate self); and emptiness (potential, the interplay of life forces, dharmakaya*) is form (the energy of potential and dharmakaya* must manifest in temporary forms). Right now, consider your surroundings. Focus your attention on just one object. What are the elements and forces necessary for it to have come into being and exist as it is? Remove just one of those elements, and contemplate the outcome.

Looking around at my own environment, my attention is drawn to the beautiful blue Chinese rug on which I am sitting. It has existed for fifty years or more and was received as an inheritance from my late mother-in-law. In each of the four corners of the rug and in the center is a depiction of a Chinese dragon, or long. Gazing at the rug, I think about the painstaking work involved in the weaving, the sheep who gave their wool, the indigo plant used to dye the yarn. I imagine my young mother-in-law acquiring the rug long ago while abroad. I think of the pilot who flew her there and the fuel necessary for the trip. I imagine the shoes she wore as she walked through the market, the paper currency she used to purchase the rug, the ordeal of having it shipped to her home in New Jersey, and now, so many years later, the human labor and commercial products needed to deep clean the rug before it could be packaged and shipped to New Orleans. Who knows if this will be its final resting place? When viewed this way, it becomes clear that the rug is not made of “rug.” It is made of vegetation used to feed the sheep, the leaves of the indigo plant, the ancient symbolism of the long, the technique of spinning yarn, and endless other “non-rug” elements. In this way, we see that the rug is bound to, and dependent upon, everything that went into making it—and dependent on what went into making those things—until we reach a point where there is no beginning and no end. The rug is empty of a separate self. We cannot truly get rid of it, even if we were to burn it or cut it up. We cannot destroy the rug any more than we can destroy the color blue.

“Through what is emptiness known? It is known through seeing dependent-arising. Buddha, the supreme knower of reality, said what is dependently produced is not inherently produced.” —Nagarjuna, Precious Garland of Advice

As we begin to make sense of interbeing, we run into its companion teaching, pratitya samutpada, or dependent arising. Form can only arise due to causes and conditions outside itself. Everything that is manifest came from something. Nothing can come into being under its own power.

It’s not so difficult to see how this is true of a rug, which cannot make itself. We might also see how our physical bodies exist due to outside causes, such as our biological parents and the oxygen we breathe. However, learning to apply these teachings to our selves, the being we call, “I,” is more challenging, but deeply transformative. Although we may think we are this or that, our selves are not solid or permanently fixed. Instead, we exist on a continuum of sensing, feeling, labeling, judging, and acting. But instead of recognizing that our ego state exists in flux, we usually fight back at it by clinging more tightly to a fixed identity.

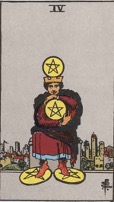

The Four of Pentacles, Copyright Arthur Edward Waite, Pamela Coleman Smith

From the Heart Sutra:

“Listen, shariputra,

form is emptiness, and emptiness is form.

Form is not other than emptiness, emptiness is not other than form.

The same is true with feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness.

Form, feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness make up the five aggregates, skandhas. They can be thought of as the basic factors of human existence that determine our take on reality. More simply, these are the filters through which we process objective experiences and shape them according to our own subjective biases.** In A Path with Heart, Jack Kornfield defines dependent arising as “the cyclical process of consciousness creating identity by entering form, responding to contact of the senses, then attaching to certain forms, feelings, desires, images, and actions to create a sense of self…Our sense of self arises whenever we grasp at or identify with these patterns.” Each of us is a collection of these constantly changing processes, and because our sense of “I” is dependent on them, our self is said to be empty.

This is not a popular statement, and I don’t recommend using it as a conversation-starter unless you’ve just broken silence at a Buddhist retreat. No one seems to want to be empty, yet we all seem to want to be free. We all want to improve ourselves, master skills, and reach meaningful goals. Once we begin to understand that emptiness is what allows us to grow, do better, be wiser, we’ve taken one step towards true understanding.

(Read more about about asmita, or ego-clinging—internal link to section in Teacher Resources)

Thich Nhat Hanh uses the relationship between water and a wave as a beautiful illustration of how we live and die, yet are never born and never die. We exist, for a time, in a physical body. We take form, and then that form dissolves. Most of us react with fear and anxiety at the prospect of death, even if we believe in something after. We panic at the specter of a void. We can’t imagine what it will be like not to be, or to be anything other than what we believe we are. But Thich Nhat Hanh offers us an elegant metaphor. If we gaze at an ocean in motion, we will observe the waves forming, rising, cresting, and dissolving. Each wave has a beginning and end, yet we know that each wave is also water. But what if the wave didn’t know it was water? Much like us, the wave would despair. It would believe that it would have to die soon. Once it crested and returned to shore, it would vanish into non-existence.

From the Heart Sutra:

“Listen, shariputra, all dharmas are marked with emptiness.

They are neither produced nor destroyed,

neither defiled nor immaculate,

neither increasing nor decreasing.

In this verse, the word “dharmas” simply refers to all things. It echoes the Law of Conservation of Mass, which states that matter and energy can neither be created nor destroyed. Most humans, cradling and protecting their self-concept, suffer under a nameless anxiety and fear. We mistakenly believe that our impermanent qualities are permanent. We must hoard them up to build a self we can show to the world. Deep down, we sense that our game is not sustainable, but we see nowhere else to go. Long gone are the childhood days of interbeing with earth and sky. Instead, we yearn for a solid identity, solid knowledge, solid laws. But this yearning is based in fear. In Thoughts Without A Thinker, Mark Epstein writes that this “…is really a place of fear at our own insubstantiality. This is why we defend it so fiercely, why we do not want to be discovered, and why we feel so vulnerable as we approach our most personal and private feelings of ourselves.” It’s no surprise, then, that so many of us shy away from concepts like “eradicating the ego,” and “no-self.” For what is hiding beyond the ego and our sense of identity? If someone asks you this question and you reply “emptiness,” don’t expect them to have coffee with you again.

But the teaching of shunyata takes us beyond face-value and further than most Western psychology. Some modern schools of psychology view certain emotions as threats, which must be controlled or tamed. Sometimes, people are encouraged to express all of their emotions in order to rid themselves of them, or conversely, to repress them altogether. There are many therapeutic approaches—as well as philosophical and spiritual ones—that employ “overcoming” the ego, and stuffing bothersome emotions out of sight, out of mind. All this slaying and vaulting over the ego misses the very heart of shunyata. Our emotions and egos are not solid enemies we can eliminate. That is an impossible and counter-productive task. Instead, we must change how we perceive and respond to these mental and emotional phenomena.

“Selflessness is not a case of something that existed in the past becoming nonexistent. Rather, this sort of ‘self’ is something that never did exist. What is needed is to identify as nonexistent something that always was nonexistent.”—His Holiness the Dalai Lama

This does not mean that our “I,” our self-concept, does not exist at all. Our subjective identity exists on the plane of relative reality, the same plane as the wave. Our self cannot be seen, but it acts in the world and creates consequences (the process of karma). Our “aha!” moment comes from recognizing that our self, like the wave, has no permanent existence. But we do exist on the plane of absolute reality, in the sense that the wave is water and has always been water, no matter what form it takes. Through interbeing and dependent arising, we are connected to all, made of all, and arise from all. While we are a wave, our empty nature allows us to move, grow, and change in infinite ways. Our physical body and our consciousness will eventually recede, but beyond the impermanent self is a fundamental life force. We return to water. Made of eternal earth, clouds, air, and sky, we cannot be destroyed. We can only be transformed. And this realization brings us profound joy and perfect wisdom, or prajñaparamita.

From the Heart Sutra:

“Therefore one should know

that Perfect Understanding is the highest mantra, the unequalled mantra,

the destroyer of ill-being, the incorruptible truth.

A mantra of Prajñaparamita should therefore be proclaimed:

Gate gate paragate parasamgate bodhi svaha.”

When we understand how our own nature and the nature of all beings and elements are intertwined, we will free ourselves from fear and illusion. The Prajnaparamita Mantra, above, means, “Gone, gone, gone all the way over, everyone gone to the other shore. Enlightenment!” (Thich Nhat Hanh, 2014).

The “other shore” is a symbol of nirvana, the state of no-fear, and is reached after a long, upstream journey against the currents of attachment and clinging. The journey may take one or one thousand lifetimes, but the ultimate end is joy. On the other shore, change and impermanence are liberating and joyful. Without emptiness, a flower would never bloom. We would never learn how to work the latest tech gadget, or grow out of a foul mood. We couldn’t witness the miracle of our children becoming adults. On the other shore, there is nothing to attain. We can simply be, and inter-be, in peace.

The Practice in Practice

The teaching of shunyata is heavy in philosophy. Here are some ways we can practice it here on the ground. The last year has been difficult for all of us, for so many different reasons, and these teachings are ever-relevant. Emptiness assures us we will adapt to change, even sudden change, or change that we perceive as negative. It reminds us that the people, things, and ways of life we may have lost in this pandemic were not destroyed, but transformed in one way or another. And in our cultural climate of deep division, the teachings of the Heart Sutra insists that the labels and attributes we impose on ourselves and others are only a cover obscuring our true nature and inherent connection with each other.

Practice 1: Renunciation and non- attachment

Through the lens of emptiness, we can perceive ourselves as being made entirely of “not-me” things. We can begin to see through the solid identities we’ve created for ourselves and recognize the beauty of change and impermanence. As we change our perspective, we learn to unbind ourselves from limiting beliefs and self-concepts. We begin to accept the constant of change. We’re able to remind ourselves that negative feelings and difficult circumstances will inevitably pass, or change. A broader, birds-eye perspective of our suffering within the web of interbeing brings us one step closer to joy.

Practice 2: Compassion

Once we realize we are made up of “not me” elements and depend on all other beings for our existence, we begin to see this is true of others, even those we do not like. We tend to bestow others with qualities like selfishness, rudeness, or stupidity, as if these traits were actually inside the person. The same applies for positive attributes, such as kindness. In both cases, we are imposing solidity onto things that are impermanent. A person cannot “be” rude. No one is made of “rude.” A person can merely act in rude ways. Eventually we realize these beings are also “empty” in the sense of having the potential to change. Then hatred and malice are not so easy to heap upon them. Instead, compassion comes more easily. We may even come to terms with our interdependence on the disliked person.

As our own feelings about others evolve, we are reminded that our feelings are not solid, either. They change, naturally. We see that feelings and attachments do not need to be slain. Guilt and regret about how we have felt or acted in the past are not useful to us for very long. Shunyata helps us be compassionate towards ourselves, too. We realize we are not our feelings; we have feelings. From a modern Buddhist point of view, our task is not to eliminate feelings but to learn new ways of being with them. We strive honor them and hold space for them while recognizing that they are impermanent and do not define us.

Practice 3: Awaken your inner child

Why is it that in childhood our boundaries between the physical world (form) and fantasy are so permeable? Children spend a great deal of time in a malleable reality that exists only in their minds—although this does not mean it isn’t real! They are less bound by concrete ideas and more open to seeing the emptiness, or potential, in the elements around them. Television, films, and books for children feature talking trees and animals, and humans who can fly and change shape like Hanuman. A child’s internal reality stretches far beyond what they can experience with the senses. Anyone who has seen children dress up or role-play knows that their identities are not fixed. They set out to discover the world with no agenda, searching for how things fit—and how they fit—into the universe. Their minds are open, egos not yet solidified. The wall of separation between them and the rest of creation has not yet gotten too high for them to climb. But by the time we reach adulthood, our thoughts become less fluid and more concrete. We adopt a solid, fixed identity, which must be reinforced and defended, reasserted again and again.

What type of imaginative play did you engage in as a child? Contemplate or journal some of the feelings you remember experiencing as you gradually discovered the world and your place in it. What did it feel like to be dropped into the middle of such a great unknown? If you don’t remember, use your imagination. Or role-play an official interview with a child in your life.

The simple act of cloud gazing awakens our imagination and teaches a gentle lesson about emptiness and impermanence as the clouds morph and parade across the sky. Try re-experiencing the magic of flying a kite. If you have access to a beach, make a sandcastle near the tide. Build it, and watch it dissolve back into the ocean.

Pick up a coloring book and don’t be afraid to color outside the lines. Draw pictures or write messages in the dirt. Climb a tree or just sit underneath one. Look for designs in the trunk. Observe the animals, insects, and plant life that are all part of our ecosystem. Stand barefoot in the grass and know that you are earth. Breathe in, and know that you are air. Spread your arms and feel the limitless potential around you, and know that you are sky.

Footnote for dharmakaya:

*In Buddhism, dharmakaya refers to the unmanifest essence of the universe from which all things are created; the life force.

Footnote for the 5 skandhas:

** We can think of form as the physical world; feeling as likes and dislikes; perception as how we label or interpret sense objects; mental formations as habitual mental reactions that lead us to perform external actions; and consciousness, our awareness of the outer and inner world. To illustrate how the Five Aggregates function, we can use a simple example of someone who doesn’t like dogs due to a negative experience in the past. Imagine that this person is walking through the park when they see a big dog (form). They experience instant aversion (feelings), mentally label the dog as a “dangerous thing” (perceptions), begin to walk in the opposite direction (mental formations) and say to themselves, ‘I am not a dog person’ (consciousness).

Interesting links:

The Social Life of Trees: How the forest communicates and supports itself (https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/12/02/magazine/tree-communication-mycorrhiza.html)

Tree.fm: Tune into forests around the world!

Learn About Forest Bathing: https://time.com/5259602/japanese-forest-bathing/

Teacher Tools

Quotes:

“When there is long, there has to be short. They do not exist through their own nature.” —Nagarjuna

“Through reflecting on dependent-arising, you will lose the belief that things exist in and of themselves.” –His Holiness the Dalai Lama

“Ordinary experience isa void that cannot be filled by anything; it is nothing but change.” —Eknath Easwaran

“You are the universe in ecstatic motion.” —Rumi

“Children have the benefit of not knowing what is not possible.” —Paul Sloane

“[A child’s] worldview is incomplete and demands discovery. They prosper because they embrace their ignorance instead of ignoring it. And they are willing to explore, investigate and put their ideas to the test because they are willing to fail.” —Sam McNerney

“Gone gone totally gone totally gone over the top, wakened mind, So, ah!”—Allen Ginsburg

“Sometimes you climb out of bed in the morning and you think, I’m not going to make it, but you laugh inside — remembering all the times you’ve felt that way.” —Charles Bukowski

“If you try to understand [emptiness] intellectually, your head will probably explode.” —Achaan Chah

“True emptiness is not empty, but contains all thing. The mysterious and pregnant void creates and reflects all possibilities. From it arises our individuality, which can be discovered and developed, although never possessed or fixed…The great capacities of love, unique destiny, life, and emptiness intertwine, shining, reflecting the one true nature of life.” —Jack Kornfield

“May I perfect the profound virtue of transcendental knowledge-wisdom, which knows how things actually are, as well as how they arise and appear, interrelate, and function.” —Lama Surya Das

“The beautiful flower does not become empty when it fades and dies. It is already empty, in its essence. Looking deeply, we see the flower is made of non-flower elements—light, space, clouds, earth and consciousness. It is empty of a separate, independent self…We have to learn to see ourselves in things that we thought were outside of ourselves in order to dissolve false boundaries.” —Thich Nhat Hanh

“There is no birth and no death, no being and no non-being.” —Buddha Shakyamuni

“If you know how to use the tools of impermanence and non-self to touch reality, you touch nirvana in the here and the now.” —Thich Nhat Hanh

“This is because that is.” —Katyayanagotra Sutra

“Nothing is born, nothing dies.” —Antoine Lavoisier

“When you ain’t got nothin’ you got nothin’ to lose.” —Bob Dylan

“Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits, and

Are melted into air, into thin air:

And like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capp’d tow’rs, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve,

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on; and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.”

—Prospero, The Tempest, William Shakespeare

“In spite of everything I still believe that people are really good at heart. I simply can’t build up my hopes on a foundation consisting of confusion, misery, and death. I see the world gradually being turned into a wilderness, I hear the ever approaching thunder, which will destroy us too, I can feel the sufferings of millions and yet, if I look up into the heavens, I think that it will all come right, that this cruelty too will end, and that peace and tranquility will return again.” —Anne Frank, The Diary of a Young Girl

“I am none of that. I am not this body, so I was never born and will never die. I am nothing and I am everything. Your identities make all your problems. Discover what is beyond them, the delight of the timeless, the deathless.” —Teacher of Jack Kornfield

“They have completed their voyage; they have gone beyond sorrow. The fetters of life have fallen from them, and they live in full freedom.” —The Dhammapada, 7.90

“I see nothing. We may sink and settle on the waves. The sea will drum in my ears. The white petals will be darkened with sea water. They will float for a moment and then sink. Rolling over the waves will shoulder me under. Everything falls in a tremendous shower, dissolving me.” —Virginia Woolf, The Waves

“Yet the Buddha, with his characteristic twist, proclaims that real joy can be found within that very stream of change. If one truly understands that life’s very nature is change, then the burning desire to wrest permanence from a world of passing sensations begins to die; and as it dies, the mind begins to taste its natural state, which is joy: not a sensation, but a state of consciousness unaffected by pleasure and pain.” —Eknath Easwaran

Further Reading:

The Other Shore, Thich Nhat Hanh

Awakening of the Heart, Thich Nhat Hanh

How to See Yourself as You Really Are, His Holiness the Dalai Lama

Interbeing: The 14 Mindfulness Trainings of Engaged Buddhism, Thich Nhat Hanh

A Path with Heart, Jack Kornfield

Thoughts Without a Thinker, Mark Epstein

Buddha Is as Buddha Does, Lama Surya Das

The Dhammapada, translated by Eknath Easwaran

The Heart of the Buddha’s Teaching, Thich Nhat Hanh

The Heart of God, Rabindranath Tagore

The Blooming of a Lotus, Thich Nhat Hanh

The Heart Sutra (Prajñaparamita Hrdaya Sutra)

A New Translation of the Heart Sutra (https://www.swanriveryoga.com/wp-content/uploads/Thich-Nhat-Hanh-New-Heart-Sutra-2014.pdf) by Thich Nhat Hanh and Commentary (https://www.swanriveryoga.com/wp-content/uploads/Thich-Nhat-Hanh-Commentary-on-new-Heart-Sutra-translation.pdf)

The Heart Sutra, translated by Thich Nhat Hanh (2012)

The Bodhisattva Avolokita, while moving in the deep course of Perfect Understanding,

shed light on the Five Skandhas and found them equally empty.

After this penetration, he overcame ill-being.

“Listen, shariputra,

form is emptiness, and emptiness is form.

Form is not other than emptiness, emptiness is not other than form.

The same is true with feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness.

“Listen, shariputra, all dharmas are marked with emptiness.

They are neither produced nor destroyed,

neither defiled nor immaculate,

neither increasing nor decreasing.

Therefore, in emptiness there is neither form, nor feelings, nor perceptions,

nor mental formations, nor consciousness.

No eye, or ear, or nose, or tongue, or body, or mind.

No form, no sound, no smell, no taste, no touch, no object of mind.

No realms of elements (from eyes to mind consciousness),

no interdependent origins and no extinction of them (from ignorance to death and decay).

No ill-being, no cause of ill-being, no end of ill-being, and no path.

No understanding and no attainment.

“Because there is no attainment, the Bodhisattvas, grounded in Perfect Understanding,

find no obstacles for their minds.

Having no obstacles, they overcome fear,

liberating themselves forever from illusion, realizing perfect Nirvana.

All Buddhas in the past, present, and future,

thanks to this Perfect Understanding,

arrive at full, right, and universal Enlightenment.

“Therefore one should know

that Perfect Understanding is the highest mantra, the unequalled mantra,

the destroyer of ill-being, the incorruptible truth.

A mantra of Prajñaparamita should therefore be proclaimed:

Gate gate paragate parasamgate bodhi svaha.”

Dharma terms and tools:

Shunyata or sunyata: (SHOON-ya-ta): emptiness, potential, inter-being.

Pratitya samutpada: Dependent Origination or Dependent Co-Arising. All things arise from countless causes and conditions. Nothing can exist on its own. Everything owes its existence to the existence of all other things.

Prajña: wisdom

Prajña (wisdom) paramita (perfection): Prajñaparamita means Perfect Understanding, or Perfect Wisdom, which is achieved by mastering the teachings of emptiness (shunyata) and dependent arising (pratitya samutpada)

Gate (gone), paragate (gone to the farther shore from which one is standing), parasamgate (completely gone to the other shore), bodhi (awakening, enlightenment), soha (swaha, amen, hallelujah)

Skandhas: Aggregates. Refers to the Five Aggregates of form, feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness. The Heart Sutra states that these are in constant cycle and none can exist without the others.

Dhatus: Eighteen realms of elements, composed of:

—6 sense organs that perceive (eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body, and mind)

—6 sense objects that are perceived (form, sound, smell, taste, touch, and object of mind)

—6 states of consciousness that result from the interaction between organs and their objects (sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch, and mind consciousness).

The contact between a sense organs and its object results in a state of consciousness. For example, ears (organ) + sound (object) = hearing (state of consciousness). None of these realms can exist by themselves.

Asmita: “Me-ness.” Attachment to our own version of reality and our own interpretations of self, others, and the world. Asmita is defining ourselves based on objects and situations that inevitably change, such as our physical body, our relationships, or our job, instead of recognizing our true self within.

Avalokiteshvara (Avalokita): Bodhisattva whose name means “lord who looks down with compassion.”

Shariputra: One of Buddha’s disciples

Dharmakaya: The unmanifest essence of the universe from which all things are created.

More on asmita, or ego-clinging: (linked from text)

The average human ego, or self-concept, is terribly fragile, built upon eggshells, stacked precariously like a house of cards. We mistake our identity for a title, or the yoga poses we can do, or the color we paint our nails. We ignore, or don’t comprehend, the fundamental impermanence of these things and spend our lives grasping frantically for the next impermanent quality to replace the one that just broke down. Somewhere in the background of our subjective experience is a low hum of constant vulnerability that compels us to cling tightly to what we think we have, or what we think we are.

For example, I identify as a bibliophile. I love books. My house is full of them, carefully arranged. You should see the dust. It is my punishment for clinging. I have an eagle eye for old, beautiful editions tucked away in used bookstores and antique shops. I take notes and make snarky comments in my modern paperbacks as I read (always in pencil). My oldest book is from 1831, a small leather-bound edition of Antony and Cleopatra, which I purchased for $3 in 2008. I am so attached to my library that I even have bookplate stickers stating that the books belong to me—as if I didn’t know! I tell myself it’s for when I loan them out to others, but I don’t do that very often. I’m afraid of losing them. Classic! (Pun incidental.)

This absurd attachment to old bound-up bits of paper is a good example of how we mistake our own identity through asmita, or “me-ness.” Asmita gives us a false sense of identity based on our possessions, our accomplishments, even our personality traits. When we try to construct a permanent self-concept, we find ourselves clinging to external artifacts in a torrent of constant change. Our bodies age. Our possessions break down. Money is spent. Relationships end. And because we believe we are made of these things, we suffer. We forget that in this web in of interbeing, we are never bereft. Even if we lose all our possessions and titles, we will always be whole. Because of shunyata, it cannot be otherwise.

Chants:

Gate gate paragate parasamgate bodhi soha.

Gone, gone, all the way gone to the shore of enlightenment together, hallelujah!

So Ham

I am That which is immortal and everlasting. That which is immortal and everlasting is me.

Asana:

—Focus on the different shapes our body takes during a single asana class, the fluidity of movement, and how even when holding a pose, or in Savasana, we are never truly at rest or changeless. The Five Aggregates (form, feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness) are in a constant flow. Every moment is fleeting, temporary. Challenge yourself and your students to find joy in this constant stream of life, without grasping onto certain poses, ideas, labels, or outcomes. In Savasana or meditation, be aware of the small movements in the body, whether it’s the rise and fall of the abdomen as you breathe or your closed eyes flickering slightly. Movement does not necessarily mean unrest.

¬

—Hip openers activate the second chakra, whose element is water, and which taps into the fluidity (and therefore impermanence) of our emotions. The hips are also commonly a place of “stuck” emotional patterns. Focus on allowing emotions and sensations to ebb and flow rather than solidify. Possible poses are Pigeon, Lizard, Malasana, Lunges, Upavistha Konasana, Agnisthambasana, and Baddha Konasana.

—Encourage the emergence of the inner child through any of the “child” poses (Balasana, Ananda Balasana), as well as poses the evoke childlike movements (Apanasana, knees to chest) or animals (Puppy Pose, Cat/Cow, Tadpole/Frog (Mandukasana), Lizard, Lion, Cow Face—and on!).

Pranayama and Meditation:

“Exercise 22: Looking Deeply,” from The Blooming of a Lotus, Thich Nhat Hanh, 1993

https://www.swanriveryoga.com/wp-content/uploads/Blooming-of-a-Lotus_Meditation.pdf

From Yoga Nidra, Swami Satyananda Saraswati, 1976:

Become aware of yourself. Find out by asking yourself, Am I aware of myself? Am I asleep or awake? See your whole body from top to toe as clearly as I see it. Try to see your body by being outside it. Ask yourself, Am I this body, the body that is eventually going to die? Now look to your senses, the five senses by which you know this world. Ask yourself, Am I these senses, the senses that die with the body?… Now try to become aware of yourself. Look to the mind, the mind by which you understand yourself and the world. Ask yourself, Am I the mind the mind that also dies?…Become aware of your aura. Ask yourself, Am I this aura whose existence is tied to the body? Look further. Become aware of the prana in your body. Ask yourself, Am I this prana? Again, look within and become aware of the existence of your consciousness by which you know that you are practicing Yoga Nidra [or meditation]. Ask yourself, Am I this consciousness? Does this consciousness still survive after the death of the body?

Look within and become aware of a golden egg in the center of your brain…a golden egg that is the seat of your highest consciousness… the seat of supreme consciousness within you at your center. Try to identify with it. Try to see yourself as the golden egg and say to yourself, Beyond the mind, body, senses, karma, nature, and everything that is physical, mental, psychic, unconscious–I am in the form of this golden egg. Say to your mind, I am that.

Mudra:

Shunya Mudra, Gesture of Emptiness

Copyright Joseph and Lilian Le Page, Mudras for Healing and Transformation

February 2021