Focus of the Month: March 2022

written by Laura Cherry

“To recover the senses, as opposed to withdrawing them, infuses a very different flavor to pratyahara by suggesting that the senses are lost or somehow need to be rediscovered or reclaimed.” —David Garrigues

When I was is pre-school, my compatriots and I were taught, correctly, that we had five senses: taste, touch, sight, sound, and smell. My parents and teachers did not warn me that in approximately 30 years, I would be attempting to withdraw them in pursuit of some Sanskrit word they couldn’t pronounce. These senses were great! I’m sure I got gold stars or some other material reward for knowing them. My senses allowed me to touch animals at the petting zoo, smell cakes at the bakery, taste Happy Meals, and look at my parents’ faces as I listened to the same “Hop Hop Hop Like a Bunny” song over and over on my tape player, the only respite for my poor parents being the rewind period.

As young children, we experience the world for the first time, everything fresh and new. Our sense impressions are only just beginning to take on fixed connotations, associations, and attachments. But as we grow, so, too, do our fixations on the sense world. Soon we beg for toys, refuse to eat boiled squash, demand candy, and throw tantrums if we can’t get our way. Gradually, unhappiness becomes a routine part of life. And soon, we hate certain things and like others, and we start constructing our personality.

Once, at the age of 2, I left my beloved Raggedy Ann doll—whom I called “Riggy”—in a hotel after my parents had checked out. They knew they had a flight to catch, but all I knew was tragedy, pure and inconsolable. My parents were desperate. The hotel wouldn’t cooperate. I remember crying in a huge store. My parents’ prayers were answered, but mine weren’t. They bought me a brand-new, identical Raggedy Ann and told me that “Riggy” had decided to go shopping that morning, had gotten lost, and now was found. I was a highly skeptical child who stopped believing in Santa by the time I was 3. I knew it was a ruse. I can still remember seeing “Replacement Riggy” up high on a shelf in her packaging. She may have looked exactly the same—the same size, same dress, same hair and face, and she felt the same to the touch—but she wasn’t my Riggy. She was just some Raggedy Ann, and I knew it.

By that age, my mind had already become quite vocal in the construction my universe. A younger version of me, whose mind was less cluttered by associations and attachment, would have accepted the match in sensory input and been satisfied that my doll was back. The variable that had changed was not the gross sensory input, but my mind’s projection of meaning onto one object versus another. This tendency to divide outer reality into “likes” and “dislikes” mires us in maya, the veil of illusion that conceals the true reality hidden behind the sense impressions. This illusion leads us to believe that objects themselves hold meaning. Instead, the qualities of objects really come from our own minds.

By that age, my mind had already become quite vocal in the construction my universe. A younger version of me, whose mind was less cluttered by associations and attachment, would have accepted the match in sensory input and been satisfied that my doll was back. The variable that had changed was not the gross sensory input, but my mind’s projection of meaning onto one object versus another. This tendency to divide outer reality into “likes” and “dislikes” mires us in maya, the veil of illusion that conceals the true reality hidden behind the sense impressions. This illusion leads us to believe that objects themselves hold meaning. Instead, the qualities of objects really come from our own minds.

If you have ever studied the Yoga Sutras by Master Patanjali, you’re probably familiar with its second verse:

1.2: Yogas-citta-vritti-nirodhah

or, “Yoga is restraining the mind-stuff (citta) from taking various forms (vrittis),” as translated by Swami Vivekananda. Put another way, by Sri Swami Satchitananda: “If you can control the rising of the mind into ripples, you will experience Yoga.”

While the word “yoga” is most commonly translated in modern times as “union,” Patanjali takes that basic definition to a higher, more specific level: yoga is a union achieved only when the mind is still, and in this stillness of thought, our senses, mind, intelligence, and ego find union with the atman, or Higher Self. This sattvic union goes by many names, including samadhi and nirvana. It is the ultimate goal of many spiritual traditions, and has inspired spiritual aspirants for thousands of years. Our primary obstacle in obtaining it getting free from the whirlpool of “mind-stuff”—thoughts, attachments, ignorance—that forever tries to pull us away from our inner Selfhood and out into the chaotic world of duality and illusion.

As yogis, we work towards this goal of inner stillness in many ways: through our asana practices, our values and behaviors, meditating, serving others (seva), and much more. According to Patanjali’s system of Raja Yoga, all of these yoga practices are laying the foundation for deep meditation, and bringing us closer to the internal state where true yoga is achieved. Patanjali’s 8 limbs of yoga build upon each other, like stairs climbing up to the highest form of freedom. They are the yamas and niyamas (moral restraints and observances), asana (steadying the physical body), pranayama (control of the breath and life force), pratyahara (sense withdrawal), dhyana (concentration-based meditation), dharana (free-flowing meditation with interruptions), and samadhi (liberation, unbroken meditation).

Many of us can understand yoga’s ethical principles, learn to breathe with skill and intention, train our bodies how to move and be still, and practice meditation in a basic fashion, even if we don’t think we are very good at it! However, the word “pratyahara,” and the idea of sense withdrawal, has not entered the common parlance or understanding, even within yoga communities. Pratyahara is sometimes called the “forgotten” limb of yoga, something to dodge on the way to meditation. At first glance, “sense withdrawal” might sound like deprivation, maybe asceticism, something we can’t do without flying off to a mountaintop to practice austerities. How can I withdraw my senses if my child is crying, or if I am desperately thirsty, or if I need to use my senses to drive home?

Even as a trained instructor of Yoga Nidra, or “yogic sleep,” which is perhaps the most well-known, widely-available, and mainstream way of accessing pratyahara today, I did not have a full understanding of sense withdrawal until I deepened my study of the Yoga Sutras and began to understand its connection to all 8 limbs, especially samadhi. Pratyahara is so inseparable from meditation that, according to David Frawley, “trying to practice meditation without some degree of pratyahara is like trying to gather water in a leaky vessel. No matter how much water we bring in, it flows out again. The senses are like holes in the vessel of the mind. Unless they are sealed the mind cannot hold the nectar of truth.”

Even as a trained instructor of Yoga Nidra, or “yogic sleep,” which is perhaps the most well-known, widely-available, and mainstream way of accessing pratyahara today, I did not have a full understanding of sense withdrawal until I deepened my study of the Yoga Sutras and began to understand its connection to all 8 limbs, especially samadhi. Pratyahara is so inseparable from meditation that, according to David Frawley, “trying to practice meditation without some degree of pratyahara is like trying to gather water in a leaky vessel. No matter how much water we bring in, it flows out again. The senses are like holes in the vessel of the mind. Unless they are sealed the mind cannot hold the nectar of truth.”

The word pratyahara in Sanskrit is made up of the preposition “prati” and the word “ahara.” Prati means against, or away from, and “ahara” means food. Ahara can refer to the food we ingest into our physical bodies, as well as the sensory information our mind receives (“mind food”). All of our dealings with the external world come to us and are moderated by our senses. When studying pratyahara, one might get the impression that the senses and sense organs are our enemy. But this cannot be true for many reasons—after all, that the teachings of yoga themselves have been transmitted to us through them. We rely on our senses to warn us when we are in danger, to tell us we are hungry and thirsty, and prompt us to procreate, to hear the scream of a child in trouble, to alert us that our house is burning, or that our food is unsafe to eat. So what is so dangerous about the mind and the sensory experience that requires such diligence and self-protection?

The concept of maya, or illusion, is present in several schools of Eastern philosophy, and refers to the inherent unreliability of our senses and mind to perceive the true nature of reality. Maya is often described as veil that skews our perceptions the world—what our mind “makes” out of sense impressions—and therefore, ultimate reality. When we live under the influence of maya, we see ourselves as inherently separate from what is around us, and cannot recognize the unity that underlies all things. Maya describes the waking dream in which most humans exist, one in which we see ourselves as self-sustaining egos separate from our surroundings, rather than fundamentally and inherently connected.

For this reason, as yogis, our relationship with the senses can be tricky. The senses may hold the key to our basic survival in the world, but they often antagonize our attempts to perceive the true nature of reality and realize the ultimate goal of yoga. So then what does it mean to withdraw the senses? And which should we withdraw, and when? And how?

Although the translation of pratyahara is often simplified into “sense withdrawal,” many teachers have delved deeper into its meaning. Judith Lasater defines it as “the conscious withdrawal of of energy from the senses.” T.K.V. Desikachar describes it as “[withdrawing] oneself from that which nourishes the senses.” David Garrigues states that “in [the practice of pratyahara] you withdraw your mind inward by refraining from the urge to immediately react to incoming sensation. You approach stilling the mind by shifting the act of sensing from an external to an internal orientation.” A great many translations liken pratyahara to a turtle drawing all its limbs into its shell.

Wild Horses

It’s true that the senses can be a serious obstacle on the path of yoga. They have the ability to divert us from the path and the practice. If the goal of yoga is union with the highest and/or stilling the mind, a process that is deeply internal, the senses impede us because they are always pulling us out from inside ourselves and into the external world. A whirlpool of mind-stuff, or citta vrittis, awaits us if we live a life of sensory indulgence or dependence that is unchecked by a higher state of consciousness. When trapped in the world of maya, or separateness, we are plagued by ignorance and its two companions, desire and aversion. There can be no peace and no stillness in such an existence.

In the ancient yogic texts, the five senses, or indriyas, are likened to wild horses pulling a chariot. If we, as the charioteers, do not firmly and skillfully hold the reins, the horses will drag us helplessly in their chaotic wake as they run in whatever direction catches their fancy. The horses themselves may even be pursuing objects in different directions, leaving the chariot paralyzed, or worse, wrecked and flipped over! Most of us have probably experienced this servitude to our senses and desires, even when our desires seem pure. Even if our intentions are good, we cannot experience deep stillness of mind and internal unity if we lack mastery over our senses and allow our minds to be jerked every which way by desire, raga, even for what seems good—and aversion, dvesha, even for what seems impure.

The Katha Upanishad explores this metaphor beautifully:

III.3-6:

Know the Self as the Lord of the chariot,

The body as the chariot itself,

The discriminating intellect as

The charioteer, and the mind as reins.

The senses, say the wise, are the horses;

Selfish desires are the roads they travel.

When the Self is confused with the body,

Mind, and senses, they point out, he seems

To enjoy pleasure and suffer sorrow.

When a person lacks discrimination

And his mind is undisciplined, the senses

Run hither and thither like wild horses.

But they obey the rein like trained horses

When one has discrimination and

Has made the mind one-pointed.

III.9:

With a discriminating intellect

As charioteer and a trained mind as reins,

They obtain the supreme goal of life,

To be united with the Lord of Love.

Similarly, in the Bhagavad Gita, the conflicted warrior prince Arjuna hands over the reins of his chariot to Sri Krishna, surrendering his desires, attachments, and suffering to the control of the Divine.

Many Minds

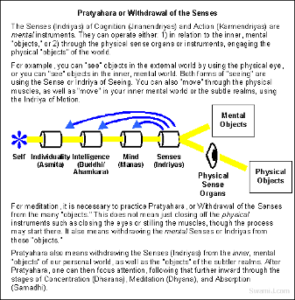

As we look deeper into the teachings on pratyahara, we begin to notice the importance of the mind, or manas, along with phrases like “the intellect,” “the ego,” “pure consciousness,” and “the atman.” Western philosophy has traditionally drawn little distinction between different stages or types of consciousness. The word “mind” typically encompasses everything that happens in the organ of our brain. Some might believe in a soul, similar to the concept of atman, but the soul is not usually seen as being related to the mind, or as an extension of the brain, but something wholly separate.

However, what we in the West might lump together as “mind,” ancient Indian philosophy has separated into subtle layers of conscious activity. In order to truly understand pratyahara, we need to understand these distinctions.

The senses, or indriyas, can be of two types: karmendriyas, or jnanendriyas. The karmendriyas are what we normally think of as the five senses: sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch, which engage with the external world. Jnanendriyas refer to sense impressions that come from our internal world, the sort of thoughts we might have even if all our senses were muted: memories, spontaneous thought, daydreams. For now, we will focus on the karmendriyas, or the senses of action.

Nine Gates (Nava Dvara)

As we move through the world, we encounter sensory impressions first through the sense organs, referred to as the “nine gates” in the Bhagavata Purana. The nine gates are our two eyes, two ears, two nostrils, mouth, and the two organs of excretion and generation. Once input reaches the sense organs, the indriyas, or senses, “read” the impression and send it to manas, or the mind.

Mind (Manas)

The mind, or manas, is the layer of consciousness that produces thoughts. These thoughts are not refined, or particularly insightful. This is the part of our mind that produces the knee-jerk reaction, the Gross! when you eat something yucky, or the hit of dopamine when you impulse buy.

Buddhi (Intelligence)

This is a stage beyond the reactionary manas where we can adjusts our thoughts with previous knowledge, insight, and power of analysis. The filter of buddhi can be used to help us temper an initial reaction, or bring wisdom to a situation, but it can also be used to strengthen an internal story we have about a stimulus, good or bad. ‘This food is gross!’ says manas. ‘This is the third time she’s served me this awful dish!’ adds buddhi.

Ahamkara (Ego)

Ahamkara, or ego, is the mind-filter of I-me-mine, determining how external events relate to our conception of ourself as an entity separate from others. It takes things personally, believes itself to be either all-powerful, completely powerless, or somewhere in between, and is responsible for a lot of tears and arguments, especially with family members around the holidays. ‘My aunt obviously hates me if she’s giving me this disgusting food, despite everything I’ve done for her. Unbelievable!’

Atman, or True Self

Finally, beyond all of these filters, we come to find our true selves, which is the real aim of yoga. When we succeed the practice, we learn to process the world using the atman, or soul, seeing things in their true nature. Learning to withdraw the external senses and direct our attention inward is an indispensable part of this process. Without it, higher states of meditation and self-awareness are not possible. Pratyahara is often described as the bridge between the “outer” limbs of yoga (moral codes, control of the body and breath) and the “inner” limbs of meditation (dharana, dyhana, and samadhi). David Garrigues writes, “Pratyahara is the bridge limb that shows you how to use asana and pranayama to find dhyana and samadhi, how to use your postures for concentrating your mind, for accurately tuning in, for reading and responding to your mental states.” Pratyahara is the turning point in our practice where we begin to move away from the external elements of our existence and turn in, pivoting our search towards our true self and connection with the Divine.

“Withdrawal is thus the transitional phase in the process of introversion that culminates in concentration, meditation, and pure contemplation.” Barbara Stoler-Miller

In practice

So how do we move this practice of pratyahara out of obscurity and onto the mat and into our practices? Yogis and teachers throughout the centuries have advocated different techniques to achieve sense withdrawal, from total sense blocking, to consciously using the senses to further our spiritual growth. For most of us, occluding the senses altogether is not a realistic goal. Instead, we may benefit more from learning to integrate sensory awareness and restraint into our practices.

One way we can do this is by consciously binding our senses to things that are sattvic, natural, or sacred. This entails paying less attention to sense traps like social media, our appearance, ego, and possessions, and substituting sense impressions that are natural, peaceful, or holy. In his translation and commentary of the Yoga Sutra, Sri Swami Satchitananda uses the example of of a Hindu temple, and how its contents bind the senses to things that are spiritual, rather than self-seeking. Our sense of smell is calmed by the burning of incense and herbs; our sense of touch, gratified by soft silks and other textiles. Our eyes gaze upon representations of deities, while the ears hear the chanting of sacred mantra. Even the sense of taste is gratified by the food offerings to the Divine, later eaten as prasad. In this approach to pratyahara, the senses are not to be denied and stifled altogether. “The ability to withdraw our senses and so control the noisy mind may sound like a kill-joy, but in reality it restores the pristine flavors, textures, and discoveries that we associate with the innocence and freshness of childhood,” states B.K.S. Iyengar. David Garrigues explores this notion even further, suggesting that cultivating our senses could even be key to our mastering pratyahara. He asks, “What if through pratyahara you are meant to master your senses by using them more completely for the enjoyment and expression of your divinity, your most conscious, profound aspects? Rather than attempting to withdraw the senses by cutting them off or diminishing their range, in practicing pratyahara you also engage the senses consciously and wholeheartedly in order to have more clarity about what to withdraw from and how to do it.” In fact, this approach is a perfect of example of pratipaksha bhavana, or cultivating the opposite.

Another approach to pratyahara is practicing non-attachment to sense objects, rather than blocking them altogether. Instead of allowing the wild horses of the indriyas to drag us around, we take the reins and decide what power, if any, sense objects will have over us. When we engage with the senses, can we do it intentionally, with full control, and without attachment? Swami Niranjanananda Saraswati illustrates this using the example of encountering a beautiful flower while we’re walking in nature. Many of of us (myself included!), would marvel at the flower’s beauty,

then pluck it, and take it home. But if we were engaging in pratyahara, we would be able to see the flower, appreciate its beauty, and then…leave it where it is and keep walking. This attitude is similar to the one Judith Hanson Lasater describes in her essay on pratyahara. Lasater writes that in her practice of pratyahara, she focuses on loosening the connection between her sense impressions and her outward reactions so that she can remain in control of her responses. She writes, “Even as I participate in the task at hand, I have a space in between the world around me and my responses to that world.” Practicing non-attachment to sense objects, or leaving that “space” between our first reaction and our final action, is one technique we can use to move towards pratyahara.

Yet another way to train the senses is to practice intentionally withdrawing one sense for a period of time. This includes setting boundaries for the senses

and observing periods of intentional sense withdrawal. I think of this “sense rest.” To rest our sense of sound, we can attend a silent retreat, or practice intentional silence (mauna, or noble silence), for a set period of time. For our sense of taste and smell, we could observe an Ayurvedic kitchari monodiet for one day, a few days, or even a week. Finding stillness in the physical body through long-held supported restorative poses can help us to surrender our sense of touch and movement. Simply closing or softening the eyes during meditation, or any other time we can do so safely, gives our sense of sight a rest and reset.

Finally, there are several more formal yoga practices designed to help us reach pratyahara, namely Yoga Nidra classes and meditation (yogic sleep), trataka (gazing at a single point), and shanmukhi mudra, in which we deliberately close off the organs of perception.

Teacher Tools

On the mat and in the practice:

Constructive Rest pose

Inviting students to leave class in mauna, or silence

Inversions, which can serve as a sensory reset

Savasana—longer Savasana and/or encouraging students to drop deeper

Starting class in Savasana

Pausing between poses or sequences to feel the body

Inviting students to close or soften their eyes in appropriate poses

Practicing shanmukhi mudra at the beginning or end of class

QUOTES:

“Through pratyahara we can journey from the outer fixation to inward revelation.” —Sharon Gannon & David Life, Jivamukti Yoga

“In practice you withdraw your mind inward by refraining from the urge to immediately react to incoming sensation. You approach stilling the mind by shifting the act of sensing from an external to an internal orientation.” —David Garrigues

“Pratyahara is the key to the relationship between the outer and inner aspects of yoga; it shows us how to move from one to the other.”—David Frawley

“We have become hostages of the world of the senses and its allurements. We run after what is appealing to the senses and forget the higher goals of life. For this reason pratyahara is probably the most important limb of yoga for us today.”—David Frawley

“Pratyahara happens by itself—we cannot make it happen, we can only practice the means by which it might happen.”— T.K.V. Desikachar

“The restraint of the senses occurs when the mind is able to remain in its chosen direction and the senses disregard the different objects around them to faithfully follow the direction of the mind. Then the senses are mastered.” (Yoga Sutras 2.54 – 2.55 as translated by T.K.V. Desikachar)

“Pratyāhāra, therefore, is the release of the urge to gobble up what comes into our senses, to leave the sense fields and allow them to be just as they are.” Richard Freeman

“As long as the senses cling to the external world, we will be trapped in the web of its impermanent and ever-changing fluctuations. The identification with the senses perpetuates spiritual ignorance and thus, causes us to mistake the everyday mind for the true Self. It is through the withdrawal from the senses by the practice of pratyahara that we begin to realize our true Self.”

“The senses are said to follow the mind in the same way the hive of bees follows the queen bee. Wherever she goes, they will follow. Similarly, if the mind truly goes inward, the senses will come racing behind.” – SwamiJ

“Notice where your awareness is. The weather outside the window, the sound of traffic. Now notice the room you are in, the colour of the walls, the temperature. Then the couch you are sitting on and the feeling of your skin in your clothes. Then your skin. Then your breath. Then your bones, your blood, your heartbeat, your thoughts, your emotions… And so on, deeper and deeper inside yourself. This is pratyahara: honing the senses in closer and closer to your experience of the world.” —Julie Peters

“Pratyahara does not mean concentration or meditation; it means reversing the flow of awareness.”—Swami Niranjanananda Saraswati

“Practicing pratyahara means remaining in the middle of a stimulating environment and consciously not reacting, but instead choosing how to respond.”—Judith Hansen Lasater

“Whenever I can notice my attempt to escape into stimulation, I am using pratyahara as a powerful tool to improve my daily life. In these moments I begin to understand the difference between withdrawing and escaping, between pratyahara and forgetting my practice.”—Judith Hansen Lasater

“If you are free from your own mind and senses, nothing can bind you; then you are really free. Even imperial power, even dictatorship, can never bind you. You are not afraid of anything.” —Swami Satchitananda

When we control the sense organs, “Then alone one begins to feel joy in being born; then one can truthfully say, ‘Blessed am I that I was born.’ When that control of the organs is obtained, we feel how wonderful this body really is.” —Swami Vivekananda

March 2022